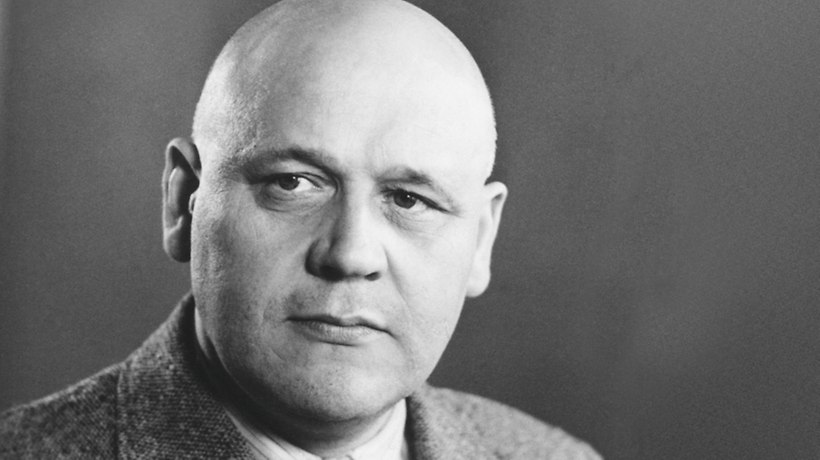

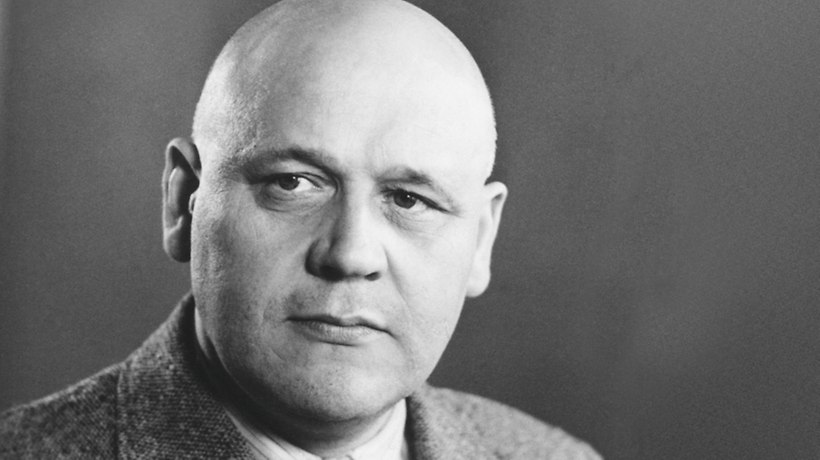

Theo Claas was the “dandy” of the family. This was his nickname among many of the workers in the company, and his brothers used it when referring to him – in a tongue-in-cheek fashion. It was no doubt an allusion to his highly proper business dress style in his position as commercial manager. But no one equated his taste for style with arrogance or aloofness.

Theo Claas, born in May 1897 as the youngest son of Franz and Maria Claas, was considered a quiet, distinguished individual. He appreciated the finer things in life, in an “English” way – correct and fashionable clothes, a polite reserve in conversation, and stylish living. He always bought his beloved cigars in the cigar manufacturing town of Bünde, which was close by. He was considered a shrewd judge of character, was always diplomatic and would invariably look for a compromise whenever necessary.

Theo Claas was the merchant of the four Claas brothers; he would probably have made a perfect bank employee in the German imperial era. He was a man of few words, but a very systematic worker. He had his career strategically planned, with a series of practical training stints in reputed, forward-looking companies, for example in the Heinkel aircraft factories in the Berlin region. At the time, Heinkel was synonymous with pioneering advances in aircraft construction – “those magnificent men in their flying machines”. He worked on aircraft development in a work team lead by Ernst Heinkel, who was nine years older than he was. Theo Claas then moved to the Rumpler aircraft factory in Berlin. Next, he travelled to Vilnius in Latvia to work on a project in the bridge-building sector. Finally, there was another quick move to Kiel to the Germania shipyard to work on the first U-boat in German history. In the autumn of 1916, the same fate befell him as his three brothers – he was conscripted.

All four brothers returned safely to Harsewinkel, but building up the factory in Harsewinkel would now mean total commitment on the part of the Claas brothers. Theo Claas could have led a busy social life at the time, but the company came first. When a few friends invited him to join their bowling club, he firmly refused. He said that a bowling club would involve unnecessary expenditure that he could not afford, and that the company first had to be doing well. He steered the young, ambitious company with a combination of consistency and thrift. As a partner of equal standing with his three older brothers, Theo ensured that there was always enough equity in the company. For him, two of life’s priorities were keeping the cigar in his mouth and saving a safe amount of water under the keel.

He also led the company through the tumultuous years after 1945, displaying the precision of a Prussian official in combination with the intelligence of a French diplomat – and with the assistance of August’s wife, Paula Claas. During this period, she held a sole power of attorney, for the eventuality of anything happening to Theo. Paula Claas had already had joint authority to represent the company for decades.

Especially in the chaotic post-war reconstruction phase, when production was initially at a complete standstill, then followed by tentative new beginnings, Theo Claas was just the right man: someone with reliable business sense and a knack for negotiating with the new bureaucracy, as well as having a deep sense of responsibility towards his employees. He showed his mettle by preventing the partial disassembly of the factory, which had remained undamaged.

He succeeded in convincing the British military authorities of the quality of the CLAAS SUPER. These combine harvesters were then tested in the United Kingdom and their quality endorsed. The company was subsequently issued with the production materials it required before any other company in Germany, and exports to the United Kingdom began.

In the first issue of the new company magazine “Der Knoter” in 1948, Theo Claas wrote: “If we had not had these export orders, we would not have been able to keep on half of our current workforce of 320.” Theo Claas loved the world of figures. With guaranteed purchase prices, precise sales analyses, and tight control of a cost-efficient approach to working to back up his arguments, he ensured that the company was on a sound footing through heated discussions with family members. He could always produce irrefutable facts and figures, and in many cases these helped steer the family decisions in the right direction. Theo Claas died at the age of 55.